It seems a long time since someone asked me a difficult question.

It could be that my understanding of ‘difficult question’ has changed over the years, but all of this came into focus for me on Thursday.

I was sitting-in on a meeting – when and where are not that relevant, suffice it to say, it was an orthopaedic trauma conference.

These are meetings orthopaedic surgeons, nurses and theatre staff run every morning in most big hospitals in the UK to review any patients admitted in the preceding 24 hours with ‘trauma’ – that is, essentially, any orthopaedic problem that needs to be treated as an emergency, such as, a broken bone or infected joint.

Traditionally, the junior doctor who has been on-call over night presents the patients to a roomful of people – this fulfils several purposes, as the doctor has seen some of the patients, they are often best placed to describe mechanism of injury, health of the patient, etc., it is also an opportunity for that doctor to learn – and this, I will return-to.

Suffice it so say, the doctor who has been working, often non-stop for 12 or 14 hours, seeing patients in A&E, in theatre and on wards, treating dislocated joints, straightening fractured limbs, although tired from all the work is in a heightened state, having to present cases to a room full of people, most of whom have more experience and have slept soundly in their own beds.

And it is here that my past came back to haunt me, for I was once that doctor, as to how long ago, I can’t be sure.

It all came-out when one of the surgeons asked the junior doctor, ‘Is it a posterior or anterior dislocation?’ The question was in reference to a patient who had dislocated their prosthetic hip joint – for the third or fourth time; an unimaginably agonising situation – fortunately, I was able, being a consultant, to sit quietly in the audience, impassive, trying not to reveal my ignorance as to the answer; the poor junior doctor, tired, a little disorientated and at the front of the room did not have an answer – so, he guessed – ‘anterior’ – it was at this moment that years of being in his position flooded back to me.

This was the way they used to teach me at medical school, and, when I was a junior doctor – the questions, placed in such a way, that to say, ‘I don’t know’ would reveal a terrible flaw in knowledge and ability, so usually, I would guess and hope for the best, which, of course, we now know, is the worst possible thing that a doctor, nurse or indeed anyone in any position of care or authority can do – not knowing and being confident to say that we don’t know is a cornerstone of patient safety.

Unless I am 100% sure that it is the left kidney, surely I should ask before I remove the wrong one, or prescribe the wrong medicine or convey the wrong information.

And it is in this very area that the secret to safe, high-quality care, and likely, safe high-quality anything – air-traffic control, teaching, directing, organising, lies – the ability to feel safe in ignorance, the knowledge that not knowing and being safe in your lack of knowledge, so long as you are open with that reality is the essence of safety.

I now know that 90 per cent of hip dislocations are ‘posterior’ – so if I am ever in that situation, if push comes to shove, I could guess, although I would like to hope that I would be confident enough to say, ‘I am sorry, I don’t know.’

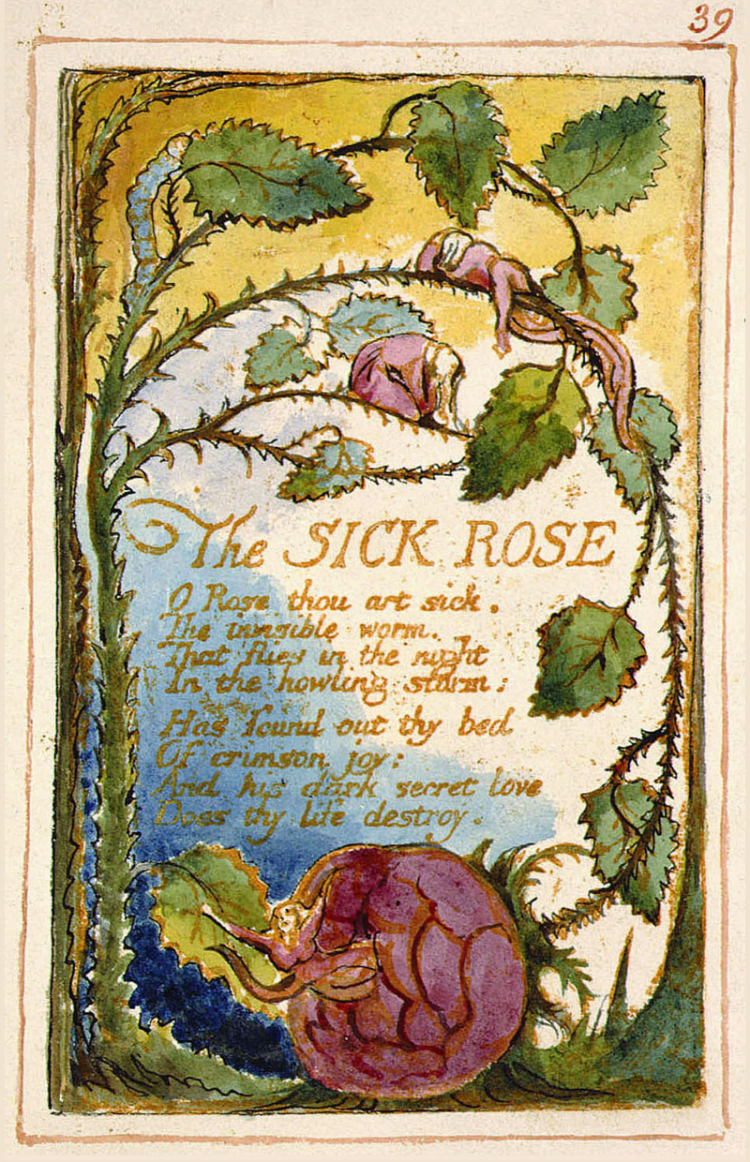

By William Blake – William Blake Archive, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8094717

© Copyright almondemotion 2016

One thought on “Innocence and experience – sorry, I don’t know”